Trinity Sunday: Our invitation to join the divine circle of love

Three in one, in closest harmony

Circled by love, in tender symmetry

Offering up the Lamb who is to be

Life for the world.

Angels are they, yet hold in meaning more

Than angels visiting at Sarah's door:

God's life itself, ready for us to pour

Grace on this world.

Help us then this circle now to join,

Our lives in newborn harmony entwine

In action mirroring the life divine

Revealed in our world.

(© Alan Amos)

This coming Sunday (15 June) we will arrive at Trinity Sunday, the climax of the Church’s liturgical year. This is reflected in the way that the following Sundays are known as ‘Sundays after Trinity’ for several months up to the point when, in November, we start to anticipate the Advent season of the following church year.

What does it mean to celebrate Trinity Sunday, and God as Trinity?

This year, as a part of our celebration of the 1700th anniversary of the Council of Nicaea, many of us have been exploring the so-called Nicene Creed, developed from the creed promoted at the Council of Nicaea with further material then added to it (especially in its final section) at the Council of Constantinople in 381.

I am probably being provocative here, but I think it is an important point to make, that actually the Nicene Creed isn’t, in my view, really and fully trinitarian! Yes, it certainly begins with an affirmation of our belief in ‘God the Father’. It goes on at some depth to speak of God the Son – because of course the discussion at the Council of Nicaea was precisely about whether we can call Jesus fully divine. The original creed of the Council of Nicaea then continues with the barest and sparsest mention of the Holy Spirit, which is then expanded in the later 381 version of the statement into the language with which we are familiar. But there is nowhere in the Nicaean Creed where the word ‘Trinity’ is actually used, nor, more importantly, are the dynamics of their relationship really explored. The later Athanasian Creed, developed in perhaps the 5th-6thcentury, will speak of ‘one God in Trinity, and Trinity in Unity’ but that phrasing was developed a couple of centuries after the Council of Nicaea, and partly in reaction to what it omitted to say.

Why I do think that this is so important? Well it all comes back to the question of what I call ‘the missing word in the Creed’, which is Love. In the Nicaean Creed the word ‘Love’ does not appear anywhere. Yet the New Testament, and especially the Gospel and Letters associated with the figure of John, make it clear the ‘Love’ is not only an attribute of God, but God’s very essence. ‘God is love, and those who abide in love abide in God, and God abides in them.’ (1 John 4.16).

The gradual Christian development of the understanding of God as Trinity can, and in my view should, be seen as an attempt to express this fundamental relationship between God and love. Because you see, love is inherently relational – it requires an ‘other’ to be its recipient, and to respond to it in turn. Yes, we believe that God loves and has loved us – our world and the creatures, perhaps especially we privileged human beings, who inhabit it. But it is also Christian orthodoxy, which is certainly implied in the Nicene Creed, that God is eternal and existed before bringing creation into being. So how did God express his nature as love before those divine acts of creation? To speak of God as Trinity, as ‘three persons in one God’ is to address this question, for it allows for mutual love to exist between all three persons of the godhead. Indeed we can then suggest that one way of looking at God’s act of creation is to see it as the ‘overflow’ of the divine mutual love between Father, Son and Holy Spirit.

I am glad we are being encouraged to sing Bishop Geoffrey Rowell’s great Trinitarian hymn as part of our celebration of ‘Trinity’ this year. The text of the hymn is given below. Even a cursory read of it makes it clear how the mutual love eternally existing within the Trinity is its central theme. The word ‘love’ appears in each of the five verses: I am particularly struck by his description of the Holy Spirit as ‘the bond of love’.

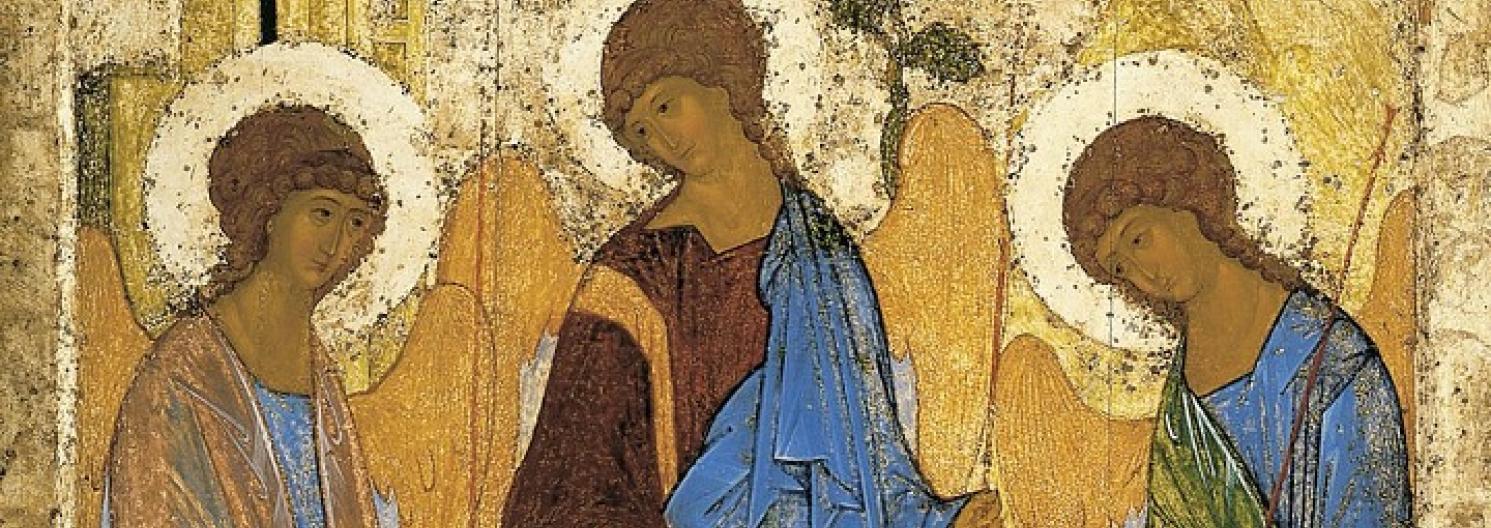

This dynamic of mutual love is also profoundly caught by the well-known and much cherished icon of Andre Rublev, often referred to as ‘the Icon of the Trinity’ but which is formally called ‘the Icon of the Hospitality of Abraham’. Created by the Russian iconographer Rublev in the early 15th century, it alludes to the biblical story told in Genesis 18 when three angelic figures visit Abraham, and after receiving his generous hospitality offer the promise of the birth of Isaac.

The mysteriousness of the story, and its ancient traditional understanding as an expression of God as Trinity is highlighted by the way the biblical text in Genesis 18.1-15 shifts back and forth between the singular and the plural when it refers to the angels. In the icon the three angelic figures, representing the three persons of the Trinity, are inscribed in a perfect circle which can be drawn round them, touching the head of the central angel and the lower feet of the other two figures. We are invited into the icon by looking first at the angel on the right (as we look at it); the angel’s green garment overlaying his blue tunic is intended to suggest the verdant, life-giving role of the Holy Spirit. The inclination of his head leads us on towards the central angel, where the robes of blue and brown remind us of the dual heavenly and earthly nature of this figure who represents the Son. The placing of this figure in the middle of the icon rightly suggests to us that the person of Jesus Christ is the essential element – the keystone – in the Church’s understanding of God as Trinity. Yet it is also significant that rather than gazing straight at us, this figure also has his head inclined to one side, which leads us on to look towards the angel on the left. The artistic genius with which Rublev painted the robes of this figure, with the light blue half hidden, half shining through an outer garment, is startling. We are approaching the mystery of God the Father – whom no one has ever seen, but who is made known to us through the Son. In the power of the Spirit we accompany the Son who is the Way to approach the ‘many mansions’ of God the Father, (notice the house etched in the background behind the angel on the left). The icon shines out with the mutual love and graciousness which is apparent in the faces and gestures of the three angelic figures.

Yet the circle does not stop here. For it encourages us to journey on and to spiritually position ourselves at the empty place which seems to have deliberately left for us at the front of the table. There is an invitation for us too – you and me – in this circle. In the language of iconography the rectangular table represents the world – that is the place for us, yet in this icon we and our world find ourselves caught up also into the circle of the divine which embraces creation. What remarkable significance is embedded in that gracious act of hospitality once shown by Abraham! His readiness to show a welcome to three apparently unknown human beings elicits in return the hospitality which is at the centre of the life of the Holy Trinity. This hospitality of God has no end and it is resonating still through eternity. It is reaching out to us, drawing us in, inviting us too to share in the feast. It is both invitation and awesome responsibility. For what is the ‘menu’ at this banquet? On the table, and marked out by the gesture from the angel in the centre, is a chalice. If you look carefully into the chalice you can see the outline of an animal. There is a hint that this is the lamb, which was offered ‘before the foundation of the world.’ (Revelation 13.8) The feast to which this icon is calling us is therefore provided through the sacrificial and self-giving love which is offered at God’s own table. And yet more profoundly still that chalice of offering is not simply an object on the table, but is echoed in the internal shape created in the space between the angel on the right and on the left. The Trinity’s witness to God’s sacrificial love for God’s world is thus embedded deep into the very heart and form of God.

Some years ago my husband, Alan Amos, wrote a short poem in which he sought to express the inner meaning of this icon. It is set out above just beneath the copy of the icon. Alan’s poem offers a reminder that to speak of God as Trinity is an invitation to us to join the circle, and to seek to mirror the divine life through our actions in God’s world.

So Trinity Sunday is not simply the culmination of the church’s liturgical year. It is also the starting-point for those ‘Sundays after Trinity’, that time in which we who profess our faith in the trinitarian nature of God are being called to live out practically in our world the love which exists at the very heart of God.

Clare Amos

Ascension Day 2025

Light of light, Love’s radiant Glory,

blessèd Trinity adored!

Well of life, our shaping story,

source of beauty, life outpoured!

As in heaven the angels worship,

‘Holy, Holy, Holy!’ sing,

let us now their praises echo,

and our lives in homage bring.

God the Father, first Beginning,

fountainhead of life and grace,

Love eternal, all-creating,

energising time and space,

seen in all creation’s beauty,

fragile flowers and stars above,

particles whose hidden mystery

praise your all-creative love.

God the Son by Love begotten,

loved from all eternity,

life outpoured for our salvation,

through whom all was brought to be,

perfect image of the Father,

God from God, and Light from Light,

healing through our human weakness,

for sin’s blindness giving sight.

Holy and life-giving Spirit,

bond of love, God’s living Breath,

presence which the Church inherits,

raising us to life from death;

drawing us to deep communion,

kindling in our hearts desire—

longing prayer for perfect union,

tears of joy and tongues of fire!

Triune God, we bring our praises,

low in adoration fall,

awesome Wonder that amazes

as our hearts now hear your call,

‘Share in me the life of glory,

lives transfigured by my Love!’

Saints on earth and saints in heaven,

in the Trinity above. (Geoffrey Rowell)