Where now for visible unity?

Revd Dr Jamie Hawkey, Canon Theologian at Westminster Abbey, was one of the Church of England delegates at the recent World Council of Churches Faith and Order conference, which took place in Wadi Natrun, Egypt, at the invitation of Pope Tawadros II of Alexandria, the leader of the Coptic Orthodox Church. Over the past century, beginning with the first Faith and Order conference held in Lausanne, Switzerland in 1927, the different branches of world Christianity have been working together to promote Christian Unity. This was clearly a major focus of this recent conference, inspired by the Council of Nicaea and its 1700th anniversary. But the recent conference also posed some difficult questions: it would not to right for Christian unity to come at the price of permitting injustice, to individuals, to particular groups, or indeed to the disadvantaged parts of our world. Unity requires reconciliation, and reconciliation is sometimes very costly. Canon Hawkey’s reflection, written specifically for the Diocese in Europe, shares some of these insights:

The breathtaking diversity of global Christianity was on display at the World Council of Churches’ sixth world conference on Faith and Order, which met in Wadi el Natrun, Egypt, towards the end of October. Just under 500 participants from an extraordinary range of Christian churches met for five days to pray, reflect and discuss questions arising from the theme ‘Where now for visible unity?’ The World Council of Churches exists to call the churches to unity. It is not intended to be some kind of ‘super church’, but rather a forum in and through which theological dialogue, and joint work on themes such as mission, justice, and worship can be pursued by an incredibly diverse range of Christian thinkers, pastors and leaders. This particular world conference took place during the 1700th anniversary year of the first Ecumenical Council – the Council of Nicaea. This great Council clarified and taught essential doctrines relating to the Trinity, and in particular to the divinity of Christ, ‘begotten, not made, of one substance with the Father.’ 1700 years on, we discovered that the Nicene Creed and its theology really does act as a common statement of faith for a staggeringly diverse range of Christian communities, including many newer, growing churches within the Pentecostal family which have frequently been seen as resistant to creedal statements.

The meeting was hosted by the Coptic Orthodox Church, referred to by one speaker as ‘the guardian of the Nicene faith’ since the days of St Athanasius, known in the Coptic Church as ‘the Apostolic.’ We were welcomed by Pope Tawadros II, and experienced the witness of that church, from the desert fathers and mothers (some of whose monasteries we visited, dating back to the 4th century), through the persecutions of the early years of the church’s life, up to the contemporary witness of Coptic Christians in worship, service, and martyrdom. Our meeting was rooted in common prayer, led by different traditions, and characterised by plenary sessions, small groups, and much animated discussion. Together, we recommitted ourselves to the vision of full, visible unity, as God’s gift rather than our own achievement, and reflected on just how far our churches have come in agreement on many of the fundamentals of our faith. The days were divided thematically as we reflected on the identity of the Church in the light of the Triune God, the Church’s mission in and for the world, and the challenge of living, visible unity. We heard voices from across the world.

What stood out? What are the areas where there are substantial opportunities for further theological and ecclesiological conversion? First, we have a shared baptism for the forgiveness of sins, and yet through that baptism, we enter a divided Church. How do we make sense of that, and what can we do to address such a contradiction? A shared baptism poses challenging questions on some habits of eucharistic sharing. What if the Eucharist is our ‘birth right’ through our baptism? Can we justify continuing to deny that to one another if we share the same faith? If we ‘walk together’ can we really not eat together, proclaiming ‘the Lord’s death until he comes’? Secondly, there are lessons from the period around the Council of Nicaea itself, even as those lessons prompt further questions. In the years following the Council, when non-Nicene Christians were reconciled to the wider catholic community, the Nicene Creed was what was required of them for that reconciliation. There are good grounds for considering that our common confession of the faith of Nicaea is sufficient for further concrete steps in Christian unity. These steps may be intermediate ones, but they are key ingredients on the journey towards full visible unity. But in order to receive this gift, our churches will themselves need to reflect on what power or practices we need to give up so that we can grow closer to one another, recognising the likeness of Christ. There is further work to be done on theological and cultural diversity, too, so we can continue to affirm that the unity of faith can be carried in diverse forms. Communion is made up of difference; interdependence is a Christian virtue.

A strong element of social justice characterised this meeting. We heard first-hand of the lives of Christians in the Middle East, and of the heroic witness in faith and action of the church in Palestine, Lebanon, Iraq and across the region. Legacies of colonialism and imperialism were examined and discussed. We became more alert to the contemporary dangers of religious nationalism in many of its guises. To move forwards together, we need to be honest about our need for repentance and forgiveness, the healing of memories, and a greater commitment to habits of justice and reconciliation. Alongside the delegates and commissioners from member churches, 100 younger theologians were present alongside us in many plenary sessions, having had their own conference during the days preceding our meeting. Their energy for the Gospel, and their commitment to the Church’s unity and to one another, will continue to animate our growth together for decades to come. The incredible diversity of this conference reminded us that Nicaea and its creed are the cornerstone of our ecumenical togetherness. The irreversible task ahead of us is nothing less than to be partners in the great work of revealing that shared family likeness, and having the courage to display that common life in Christ in our church structures, and in our habits of prayer and action.

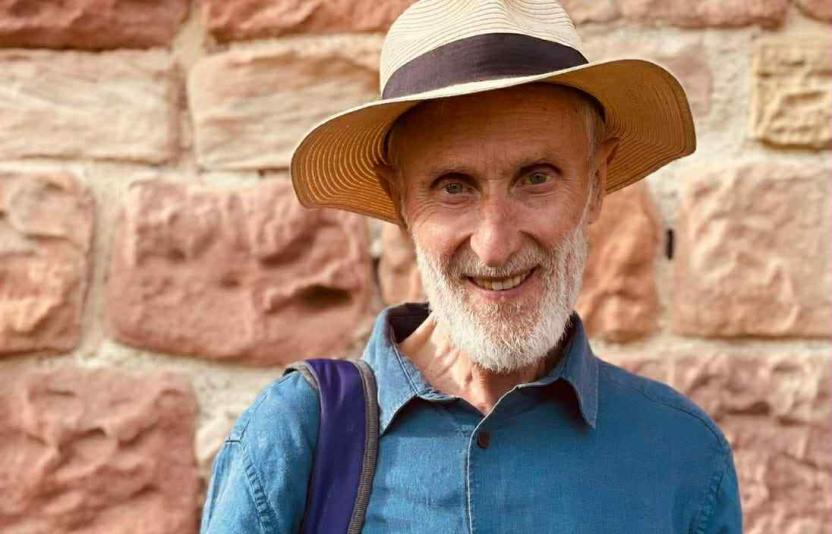

The Revd Canon Dr Jamie Hawkey is Canon Theologian of Westminster Abbey, and represented the Church of England.